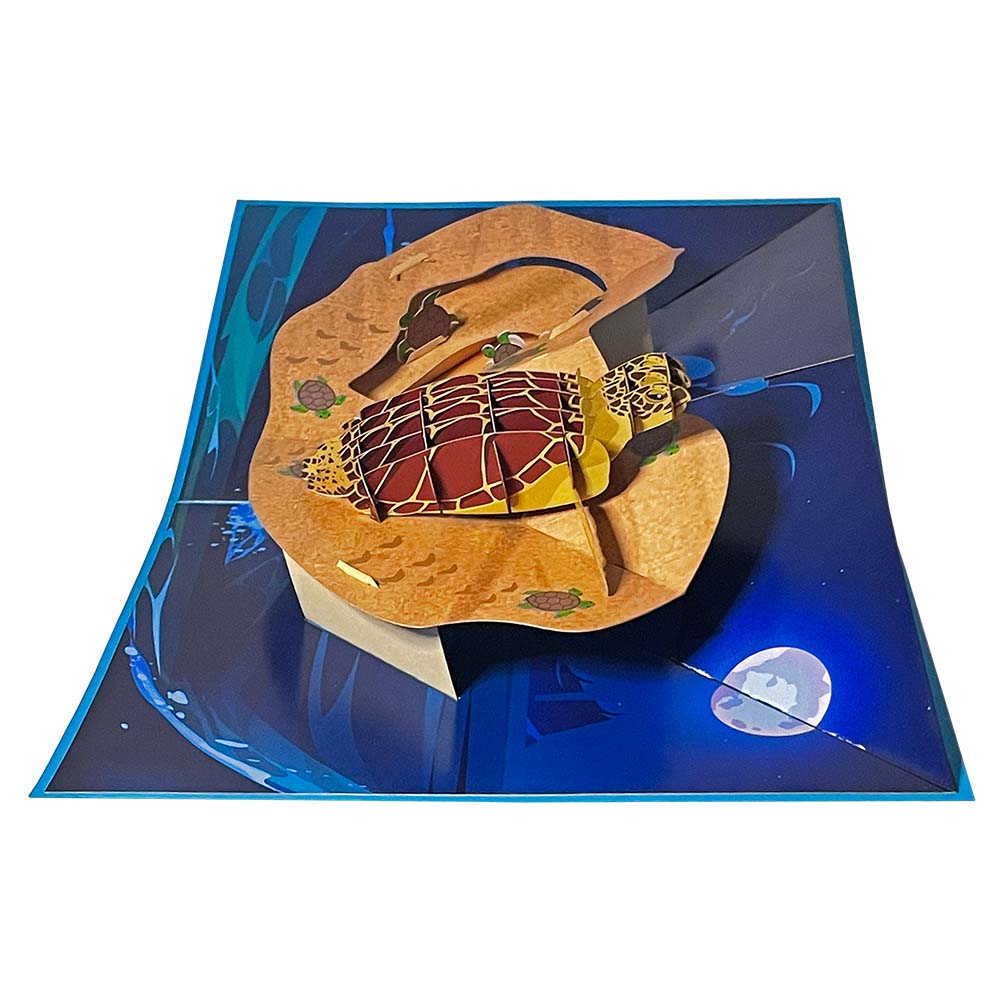

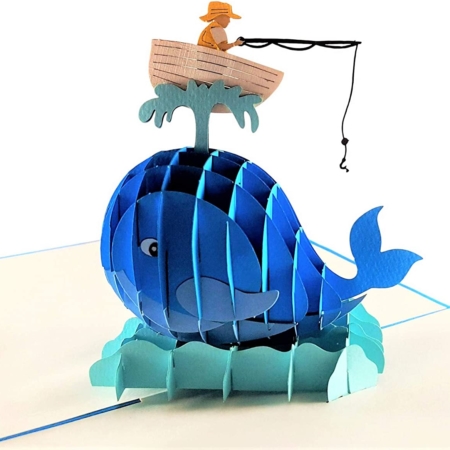

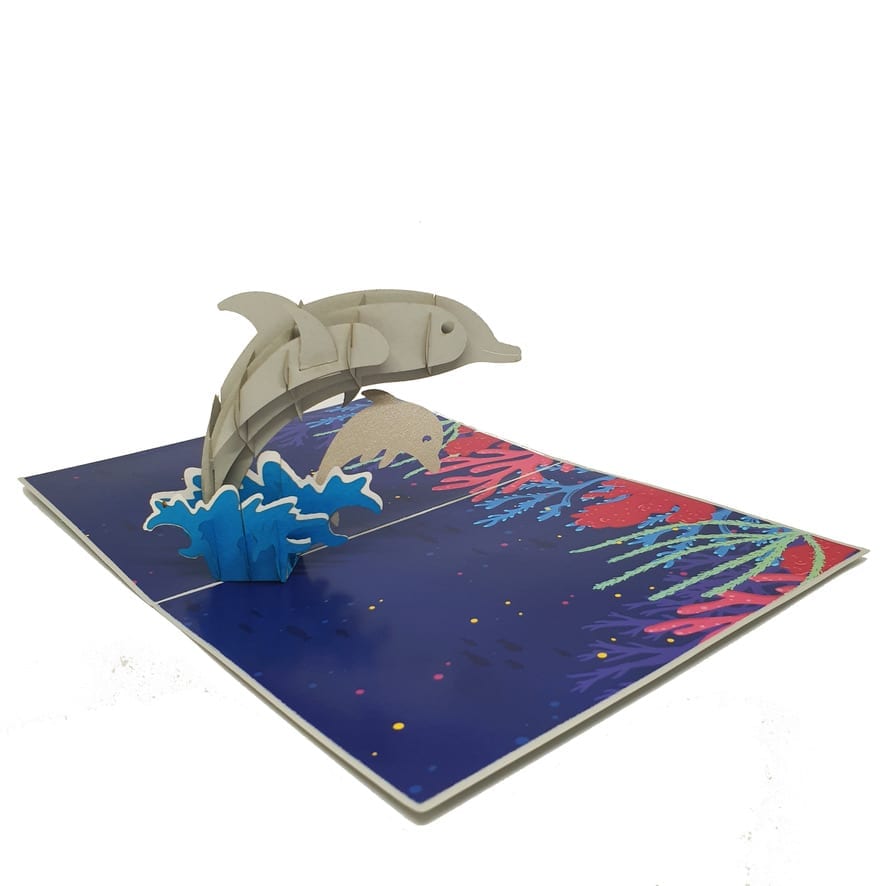

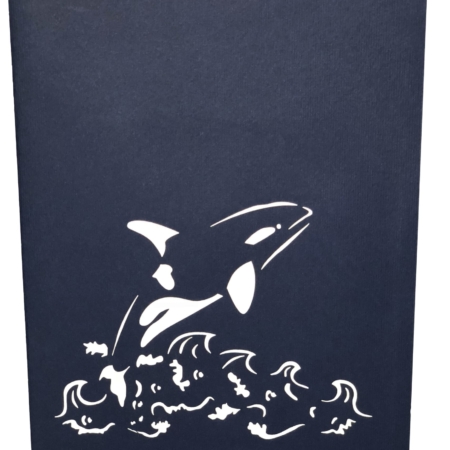

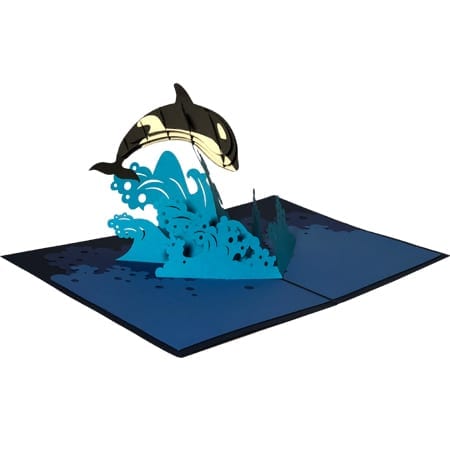

Description

How do baby sea turtles hatch?

Baby sea turtles hatch from their nest en masse and then rush to the sea all together to increase their chances of surviving waiting predators.

In summertime when the weather is warm, pregnant female sea turtles return to the beaches where they themselves hatched years before. They swim through the crashing surf and crawl up the beach searching for a nesting spot above the high water mark.

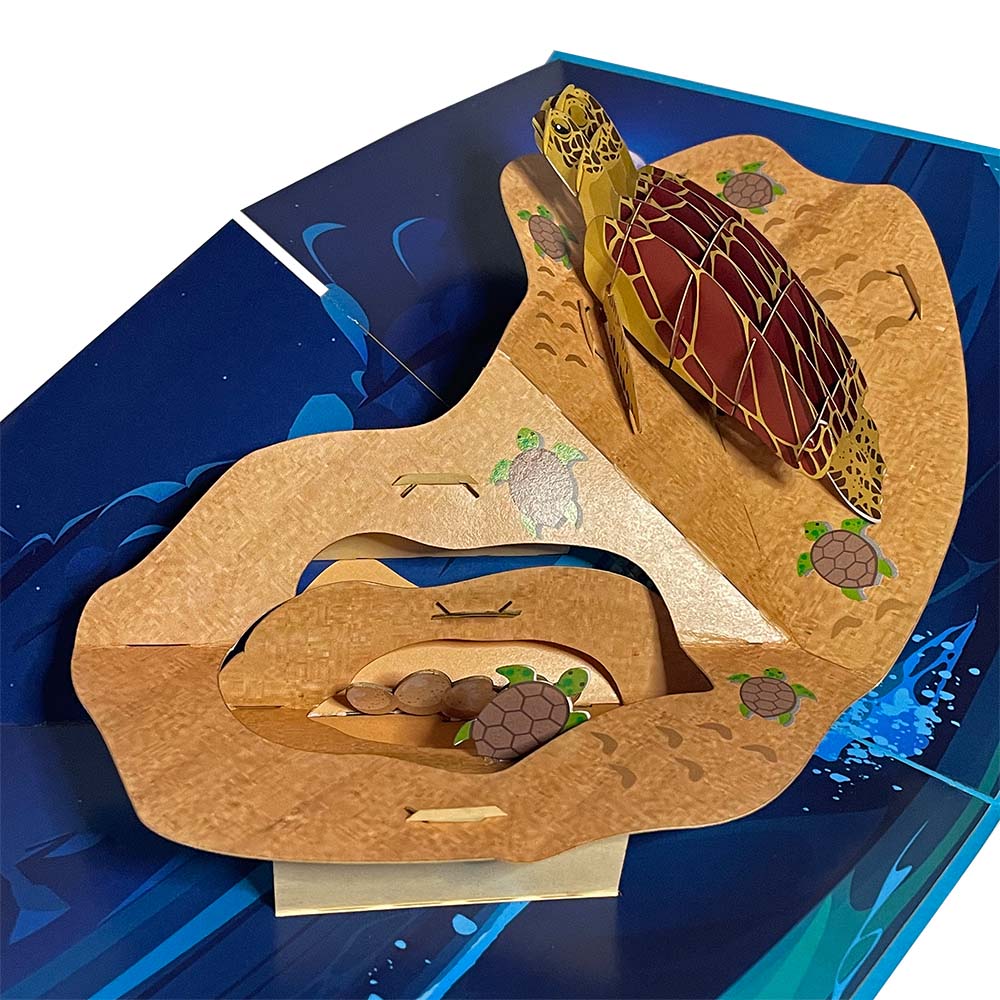

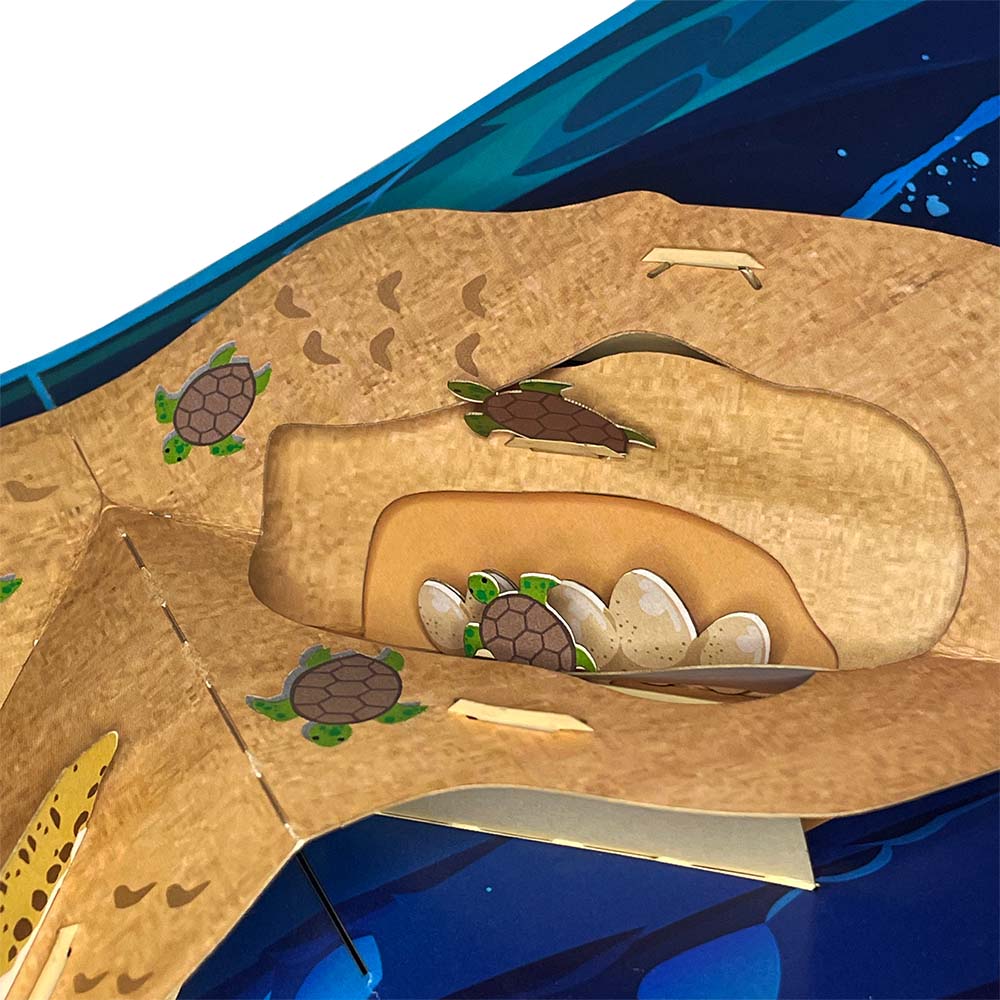

Mama digs a nest in the sand.

Using her back flippers, mama digs a nest in the sand. Digging the nest and laying her eggs usually takes from one to three hours, after which the mother turtle slowly drags herself back to the ocean.

The mama sea turtle lays 50 to 200 leathery ping pong ball size eggs, which incubate in the warm sand for about 45 days. The temperature of the sand determines the genders of baby sea turtles, with cooler sand producing more males and warmer sand producing more females.

Baby sea turtles hatch.

When the tiny turtles are ready to hatch out, they do so virtually in unison, creating a scene in the sandy nest that is reminiscent of a pot of boiling water. In some areas, these events go by the colloquial term “turtle boils.”

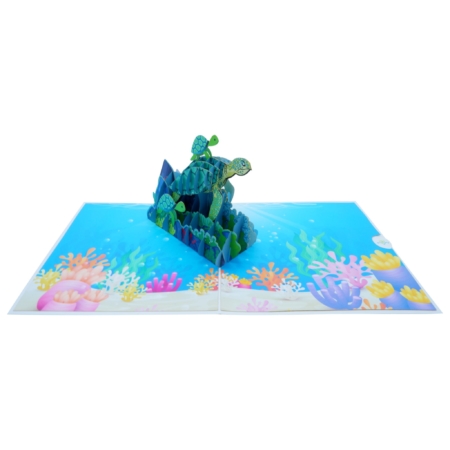

Once hatched, the baby turtles make a desperate dash to the sea, via the downward slope of the beach and the reflections of the moon and stars on the water. Hatching and moving to the sea all at the same time help the little critters overwhelm waiting predators, which include crabs, sea gulls, foxes, raccoons, and wild dogs.

Once in the sea they face other predators: fish, dolphins, sharks, sea birds. Those that make it through the gauntlet swim to offshore seaweed “islands” where they will spend their early years mostly hiding and growing.

These seaweed havens are made of sargassum, a type of large brown algae that floats in island-like masses and never attaches to the seafloor.

Watching the hatchling:

Watching a baby turtle (known as a “hatchling”) struggle out of the nest and make its way to the water is an emotional experience. Everything from footprints to driftwood and crabs are obstacles, though this gauntlet is important for its survival. Birds, raccoons, and fish are just a few of the predators these vulnerable creatures face; some experts say only one out of a thousand will survive to adulthood under natural conditions.

After an adult female sea turtle nests, she returns to the sea, leaving her nest and the eggs within it to develop on their own. The amount of time the egg takes to hatch varies among the different species and is influenced by environmental conditions such as the temperature of the sand. The hatchlings do not have sex chromosomes so their gender is determined by the temperature within the nest. Warming trends due to climate change may cause a higher ratio of female sea turtles, potentially affecting genetic diversity.

Emergence:

The hatchlings begin their climb out of the nest in a coordinated effort. Once near the surface, they will often remain there until the temperature of the sand cools, usually indicating nighttime, when they are less likely to be eaten by predators or overheat. Once the baby turtles emerge from the nest, they use cues to find the water including the slope of the beach, the white crests of the waves, and the natural light of the ocean horizon.

If the hatchlings successfully make it down the beach and reach the surf, they begin what is called a “swimming frenzy” which may last for several days and varies in intensity and duration among species. The swimming frenzy gets the hatchlings away from dangerous nearshore waters where predation is high. Once hatchlings enter the water, their “lost years” begin and their whereabouts will be unknown for as long as a decade. When they have reached approximately the size of a dinner plate, the juvenile turtles will return to coastal areas where they will forage and continue to mature.

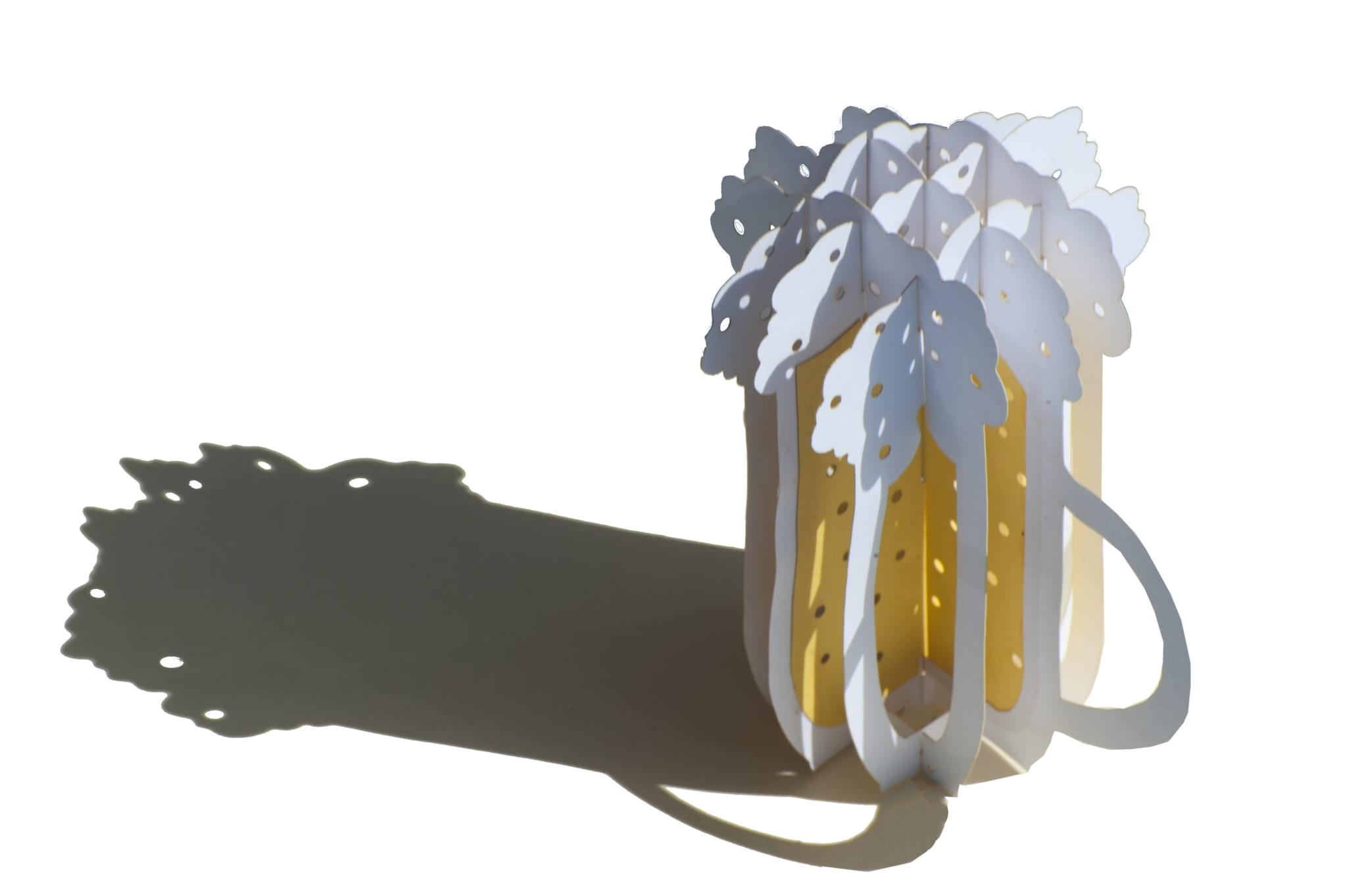

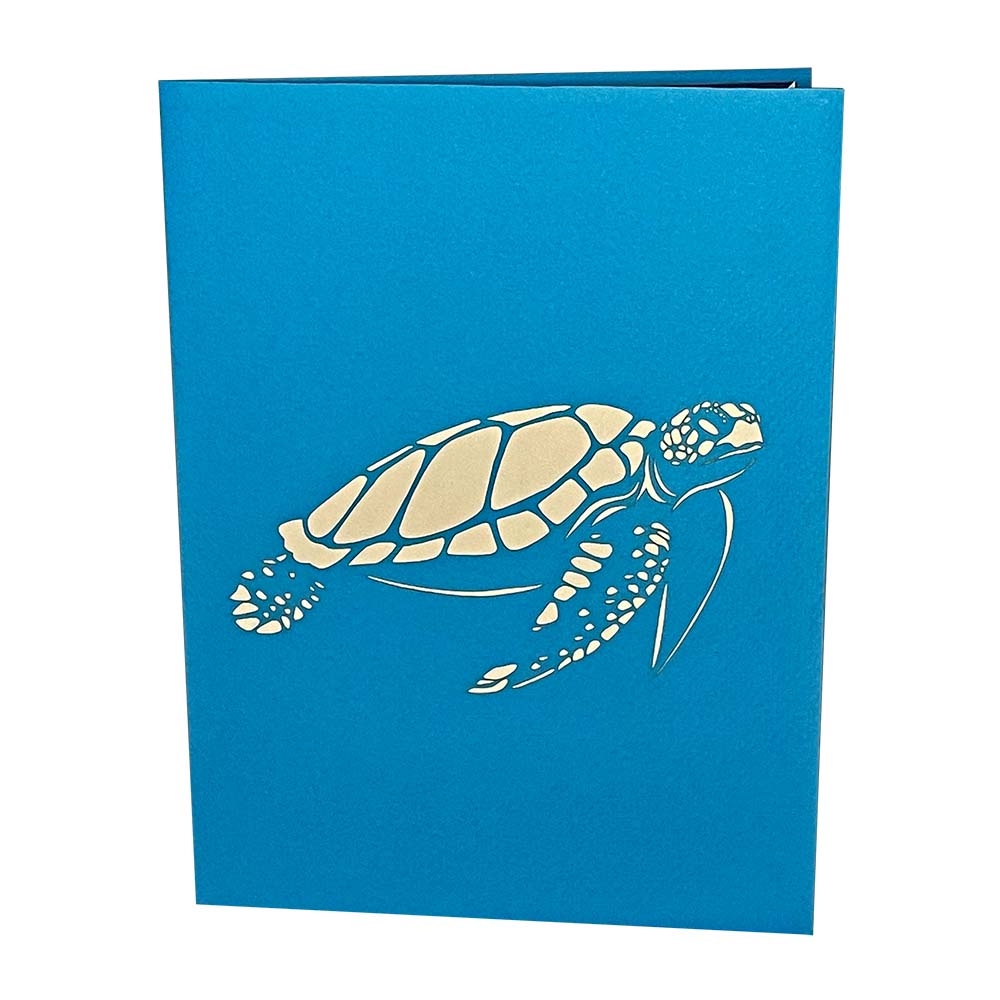

See also Endangered Sea Turtles pop up card.

Join the “Too Rare To Wear” movement, and never buy items made from endangered sea turtle shells.